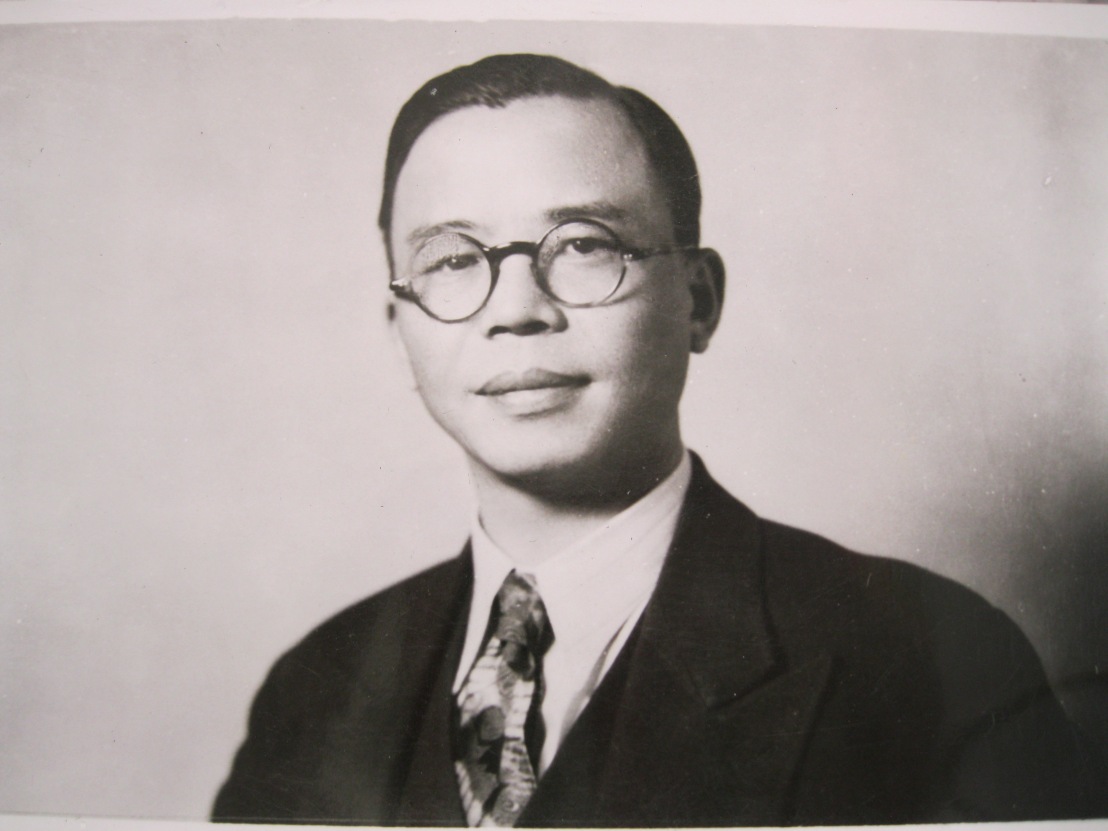

I have a famous person to profile today! T. F. Tsiang (蔣廷黻, pinyin Jiǎng Tíngfú) was not only a student during the time of the Boxer Indemnity Scholarship program, but he went on to serve the Republic of China’s government and was a delegate to the United Nations. This means that there is a ton of information and newspaper articles available about him, his life, and his work, unlike many of my other Indemnity Scholars. To keep this from being an entire novel, and to avoid retreading the same ground that others have already examined thoroughly, in this post I will concentrate on T. F. Tsiang’s university life and studies, as well as his personal life.

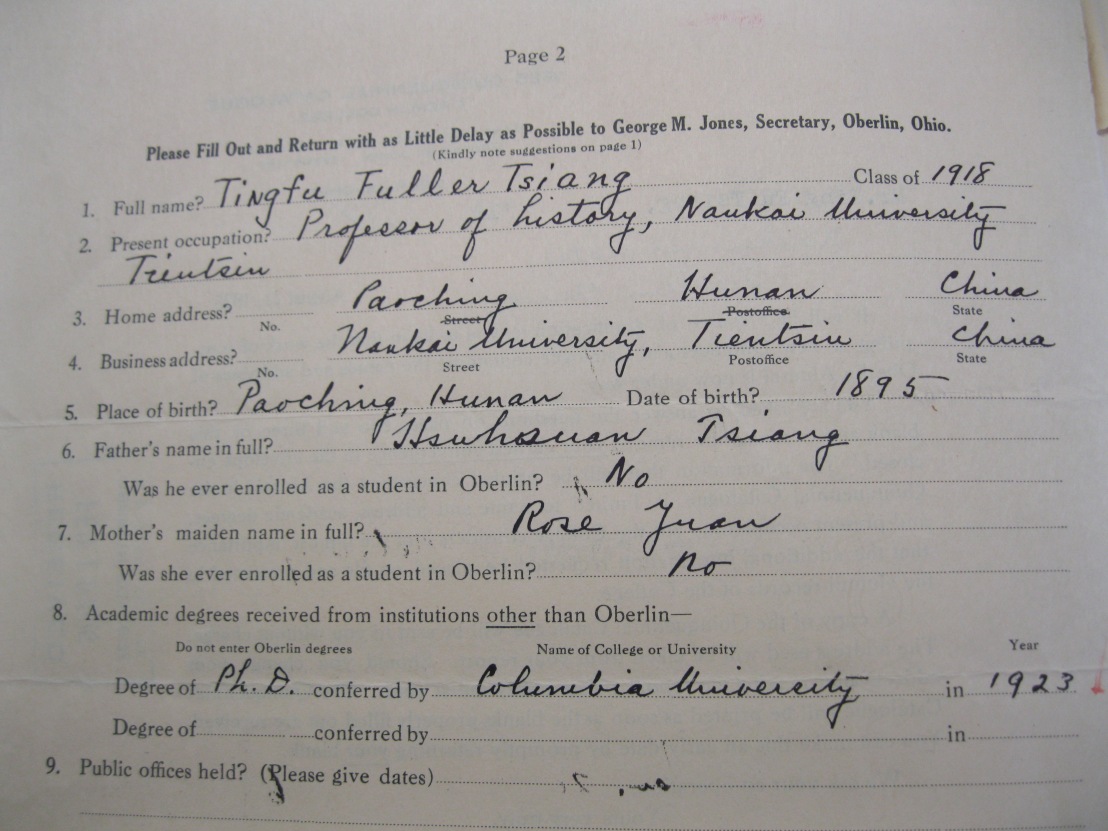

T. F. Tsiang was born on 21 October 1895 in Shaoyang, which is in Hunan Province (1921 Who’s Who of American Students). This town was also called Paoching (1936 Who’s Who in China), and he often self-reported “Paoching” as his hometown. His father was listed as “Hsu H” and his mother “Meiyi Yun” on his US Social Security information from 1965 (link to record), but his father’s full name was “Hsuhsuan” (alternately written as “Shu Shai”) and his mother went by the Western name “Rose”. This was possibly a translation of her Chinese name, which may have been Meigui (玫瑰). His father was a farmer who also owned a general store in Paochang (Oberlin Alumni Magazine, Feb 1966). He had one brother that I know of: Leo Tsiang, another returned student who I will be profiling later. Their address was “East Road of Shaoyang”, which possibly gives you a sense of the size of this village.

As a boy in Hunan, T. F. Tsiang attended Chinese schools, as opposed to Western missionary schools: first Minteh elementary school in Changsha, then Yichi School in Siangtan (1940 Who’s Who in China, 13). Then, in early 1912, at the age of 16, he left China to study in the United States. At this time, he didn’t seem to have any government scholarship or Western educational training at all. What’s more, he came completely alone; there were no other students who boarded the SS Persia in Shanghai as he headed off to Kansas City (link to ship’s manifest). His US contact was listed as “Miss Rose Tucker, Park College, Kansas City, MO” – most likely a teacher at the school he was about to attend.

He attended Park Academy for several years, although the first he appears in the Chinese Students’ Association records are in the 1914 and 1915 directories, listing him as living in Parkville, MO. He entered Park Academy as a second year student (Catalogue 1911/12, pg. 86) and proceeded to his third year on time (Catalogue 1912/13, pg. 87). He began to earn some academic recognition for his talents in his third year, as well as his fourth year (Catalogue 1913/14, pg. 73). In 1913, he earned a prize for getting the highest grade in beginning German (pg. 60). And in 1914, despite having been at the school only 2 years, and having limited prior training in Western subjects, he earned the highest grade of the Fourth Year English class, the highest grade of the Fourth Year Geometry class, and scored the highest on the yearly exam of “Mythology, History, and Translation of Virgil”. (General Catalogue 1914, pg. 59).

He didn’t stay at Park College for his undergraduate studies; instead he entered Oberlin College. There are some references to him winning a Hunan Provincial scholarship for his studies at Oberlin, but this would have meant that he returned to China between his high school studies and beginning college. Not only do I not have any records of that departure and return, I also have a lot of references to T. F. Tsiang’s money troubles while he was at Oberlin, so I doubt he had any Chinese government support.

He was a freshman in the 1914-1915 year, living at 124 W. Lorain Street (Catalogue 1914/15, pg. 325). He quickly became known to the Oberlin community, as this letter from T. F. Tsiang’s Oberlin file indicates:

Nov. 30, 1914

My dear Mr. Bohn,

I don’t know Mr. Tsiang very well but he is on the membership committee of the Cosmopolitan club and I have met with him a couple of times. I will confess that he attracts me rather more than most of the Chinese students. It may be that he is just a little more American than most of the rest, but I think that the effort to get across is commendable. Even if he were loafing a little I don’t believe it is serious. If you learn anything of that sort please let me know and I will follow it up.Sincerely,

H. A. Miller

T. F. Tsiang took classes during the summer session of 1915 (Catalogue 1915/16, pg. 366), but he struggled to make ends meet. A letter written on 7 June 1915 about his situation reads,

Dear Mrs. Crumbie:-

I have taken pains to find out all I could about Mr. Tsiang’s present situation; and, in view of the fact that our exceedingly unjust anti-Chinese laws make it impossible for him to do manual labor in order to earn money [ed. note: this is referring to the Chinese Exclusion Act], it would be very generous and acceptable if you could provide the $25. he needs for the summer session, made necessary by the closing of the club where he hoped to be able to help meet the cost of board and room.

It seems the $25 was not forthcoming, or perhaps was not enough to sustain T. F. Tsiang for the rest of the summer, because in a letter dated 27 July 1915, Mr. Bohn remarks,

My dear Mr. Robb:-

There are two young men in our Summer School, Chinese, who have spoken to me about their desire to find employment on a farm near Oberlin for the rest of the summer, after Summer School closes, August 5th. One is Mr. H. G. Tsen, a mature young man, of very fine character and personal qualifications. The other is a younger boy, Mr. T. F. Tsiang, in whom I am much interested. Neither of these men have had experience in farm work, but want to find a place where they can earn their board and something more until school opens. They are willing to do any kind of work, I understand, and would not expect anything like full wages [ed. note: most likely because this work would be “under the table” as per the Chinese Exclusion Act]. I shall appreciate it if you will let me know soon if you know of anybody who would care to make use of the services of one or both of these men.

By his sophomore year, T. F. Tsiang had moved to 136 Woodland Avenue (pg. 329). He took summer classes again in 1916, living at 314 Reamer Place (Catalogue 1916/17, pg. 372). In his junior year, he lived in the “Men’s Building” (Catalogue 1916/17, pg. 334). The Selective Service caught up with him in the summer of 1917, listing his address as 181 West College, Oberlin (link to WWI Draft Card). And in his senior year, he lived at 100 Professor Street, as evidenced in both the 1918 CSA Directory and the Oberlin Catalogue (Catalogue 1917/18, pg. 204). He graduated with his BA in Psychology in the spring of 1918 (Oberlin College Yearbook 1919, pg. 42).

He would be going on to grad school, but before he did so, he took a year’s job in France, working as YMCA secretary with the Chinese labor battalions (Alumni Magazine, Feb. 1966). He returned to the US in the summer of 1919 to begin his graduate work in political science at Columbia University in New York City. As of the 1920 Census, he lived at 415 W 115th Street in lodgings owned by a female portrait painter from Massachusetts. His fellow boarder was another Chinese man who worked as the foreign secretary for the local YMCA (link to 1920 Census). He moved to 505 W 124th Street by 1921 (Catalogue 1921/22, pg. 327).

He may have been involved in the Washington Naval Conference, like T. L. Li and C. Y. Wang (Shen Bao, 6 Dec 1921, pg. 10). Then, he returned to Columbia to finish his PhD, with a dissertation titled “Labor and empires”. His thesis successfully defended, he returned to the East, stopping at Yokohama, Japan on 26 June 1923 to get married to a woman named Nyok Zoe Dong. She was also a returned Chinese student who was in Massachusetts, and I’ll eventually do a post on her as well. They would go on to have 4 children.

The rest of T. F. Tsiang’s life can be divided into two phases: his career as an academic, and his career as a diplomat. The academic career came first, with him teaching history at Nankai and Tsinghua Universities, as well as a stint overseas lecturing at London and Oxford Universities from 1929 to 1935. Starting in 1936, his political life began with his appointment as the ambassador to Russia. He kept this post for about a year (New York Times, 26 Dec 1937), then returned to China to take on various government projects, before being appointed UN ambassador in 1947. He was an accomplished diplomat and a leading academic in the Republic of China.

“I suppose you know that T. F. Tsiang, as he is called in China, is Minister without Portfolio in Chiang Kai-shek’s cabinet,” K. H. Salter wrote in a personal letter in the early 1940s. “A Chinese scholar…told me that Tingfu’s activities and his value to China could never be described by that or any title. He is one of China’s very greatest men…”

“Numerous clippings have come of a column by A. P. writer, J. H. Roberts,” an Oberlin College Alumni Magazine article from 1959 read. “The column is headed ‘Dr. Tsiang Says…’ and quotes Ting-fu Tsiang on the Laotian troubles. Then the writer goes on to say, ‘”Dr. Tsiang Says” has become a familiar remark in United Nations circles whenever Asian issues are being discussed. He is not only one of the senior members of the UN diplomatic corps, but also one of the most experienced.'”

When Japan joined the UN in 1956, T. F. Tsiang gave a statement:

However, things in T. F. Tsiang’s personal life were not going so well. His diplomatic duties had him away from home for months at a time, and I found numerous records of him entering and leaving the US, often within the same year. During one of these returns, on 23 December 1948, T. F. Tsiang’s photo was taken and posted in the paper, with the caption “T. F. Tsiang and wife return from Europe”. The only problem was, his wife N. Z. Dong was at home in New York, and the woman in the photo was Hilda Ung-chung Shen. Probably very alarmed, N. Z. Dong contacted her husband . . . and discovered that he was now her ex-husband, as they had apparently gotten a Mexican divorce (New York Times, 28 Jan 1949: 18). This divorce had happened the previous 27 April, and T. F. Tsiang had remarried Hilda Shen in the interim (Chicago Daily Tribune, 28 Jan 1949: A8).

Furious, N. Z. Dong sued T. F. Tsiang, who subsequently claimed diplomatic immunity. The suit reached the Supreme Court of New York, where the judge agreed with T. F. Tsiang and threw the suit out (New York Times, 08 Feb 1949: 13). N. Z. Dong then petitioned the UN to intervene (The Washington Post, 25 Mar 1949: 25; Shen Bao, 26 March 1949, pg. 3). Still, the divorce stood.

T. F. Tsiang continued to work as a diplomat, becoming the Republic of China (Taiwan)’s ambassador to the US in the final years of his life, before passing away from cancer on 9 October 1965, in New York Hospital, New York City (Alumni Magazine, Feb 1966). If you want to know more about this incredibly accomplished and super interesting figure from Chinese history, check out these sources:

eBay – this is a photograph with a lot of decent information about T. F. Tsiang in the description

Interestingly enough, Hilda Tsiang nee Shen, was my grandaunt. I was intrigued about this part of family history from family photograph. I saw a picture of her with her husband during his appointment to the United Nations.

LikeLike

Hello! That’s super interesting; it’s great to hear from you!

LikeLike