Today’s student is Lingoh K. Wang (王麟閣, pinyin Wáng LínGé), a student who seemed to be on a mission to attend every single university in the United States in his seven years in the country, then visit every single country as Chinese consul after he graduated.

L. K. Wang was born in about 1881; the University of North Carolina 1924 Alumni History lists his birthdate as 24 Dec 1882 (pg. 664). He was born in Peking (Beijing), more specifically in Daxing, which at the time of his birth was part of the now-defunct Chihli province. I have surprisingly little information about his early life; he isn’t in any of the Who’s Whos I have access to, and he didn’t attend St. John’s or Tsinghua. According to a completely unsourced Chinese webpage, he attended 公立京師大學堂, which translates to a public Beijing university school – probably not Beida, but it’s possible he attended a preparatory school that was affiliated somehow (王麟閣介绍). I do have some documentation from this school, which I am currently processing – so stay tuned for a possible update. The Chinese source also states that he got a BA in literature from this Beijing public school. After graduating, he headed to the United States to study as a private student, meaning that he received no scholarship money.

I haven’t been able to find any entry paperwork for L. K. Wang either, but he entered the United States some time in 1905, headed to Boston and enrolled in MIT as a special student. He was a member of the MIT class of 1909 (MIT Alum 1912, pg. 513), and he was definitely there in December of 1905, living at 16 St. James Avenue (Bulletin of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Catalogue of the Officers and Students (Dec 1905), pg. 392). He studied Mining Engineering and Metallurgy (MIT Alum 1912, pg. 428). However, he wasn’t at MIT for very long, because he shows up in the 1905 Mei Zhou liu xue bao gao (美洲留学报告) as a student at Ohio Wesleyan studying Chemistry. He was still planning to graduate in 1909 with a BS. Despite this, the Ohio Wesleyan University catalogue lists him as a “subfreshman”, or preparatory school student (Sixty-Second Catalogue of Ohio Wesleyan University (1906), pg. 168; pg. 182). There’s also a discrepancy in his addresses: the 1905 Chinese Students’ Association source lists him as living at 226 W Williams in Delaware, Ohio, while the Ohio Wesleyan Catalogue lists him at 20 Montrose.

After less than two years in the United States, and as many colleges, L. K. Wang moved again. This time he was ready to enroll as a freshman. According to the Chinese Students’ Bulletin, the precursor to the Chinese Students’ Monthly, L. K. Wang entered Cornell in the fall of 1906 (Vol. 2 (Dec. 1906), pg. 10), enrolling as a freshman to study Civil Engineering (The Register, Cornell University (1906-1907), pg. 640). He quickly got involved with the Cornell Cosmopolitan Club, giving a speech on “The Proposed Constitution of China” at a meeting that fall (Chinese Students’ Bulletin, Vol. 2 (Jan. 1907), pg. 32). Giving speeches was something he did regularly; in March or April of 1907 he gave another speech to the Cosmopolitan Club about Peking, complete with lantern slides (Chinese Students’ Bulletin, Vol. 2 (Apr. 1907), pg. 106). The 1907 Directory gives an address of 310 “Henstis” Street – probably Heustis Street – in Ithaca with an anticipated graduation year of 1912.

It seems like he was planning to stay at Cornell, but then fate intervened. The November 1907 edition of the Chinese Students’ Monthly stated that the Ithaca Club was sad to lose L. Wang, one of their “faithful members”:

Mr. L. Wang, on account of ill health, has gone to the University of Colorado, where he is taking a course in Finance and Administration. We are, however, pleased to note that he is enjoying the best of health there.

– Vol. 3 (Nov. 1907), pg. 10

L. K. Wang enrolled as a sophomore in the College of Liberal Arts at the University of Colorado, Boulder, living at 1107 13th St., an address repeated by the Chinese Students’ Monthly (Vol. 3 (Dec. 1907), pg. 89; Catalogue of the University of Colorado, Boulder (1907/08), pg. 262). He took classes at UC Boulder in the summer of 1908 as well, moving to 1307 College Avenue for the semester (Catalogue of the University of Colorado, Boulder (1908/09), pg. 307). However, he wasn’t enrolled for the next regular academic year.

Instead, in 1909 he shows up in a city directory from Colorado Springs, living at 805 N Cascade Avenue (ancestry.com link ). Perhaps his health had gotten worse; Colorado Springs was a popular health resort for tuberculosis. He didn’t completely stop his schooling, though, enrolling at Colorado College as a special student (The Pike’s Peak Nugget 1910, pg. 110). The health crisis was brief, and he was enrolled again at UC Boulder by 1910, living either at 1119 Broadway (Catalogue of the University of Colorado, Boulder (1909/10), pg. 276) or 1061 14th Street in Boulder (Aldama, A., et. al., pg. 166).

1910 was L. K. Wang’s junior year at UC Boulder, and it was a tradition at many universities at the time that the junior class was in charge of the school yearbook. This means that L. K. Wang was mentioned more than just his name and hometown. The yearbook contains this humorous article on page 80:

The following startling record, hermetically sealed in a ketchup bottle, was found floating off the coast of Coney Island by Professor Boskerino Nafe, an eminent sword-swallower, whose word has never been doubted in scientific circles….The record was found to be a history of the famous class of 1911, and tells of the doings of the renowned members of said class; some have achieved fame, others have acquired it, while the rest have had fame thrust upon them.

Lingoh Wang is with the Barnum and Bailey Shows, and does the “Dash of Death” down an incline, with two flip-flops in the air. He used to “Leap the Gap” from breakfast to lunch with a sandwich at the Co-op, and so received his early training.

There’s kind of a lot there. I did consider whether this was meant to be a racist caricature of a Chinese acrobat, but the references to the sandwich seem much more individual, and this is not going to be the last reference to L. K. Wang’s weight and eating habits.

He may have moved once more within Colorado – the 1911 Eastern Section Directory listed his address as 904 14th Street in Boulder – but then at the start of his senior year, he left the state entirely and transferred to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

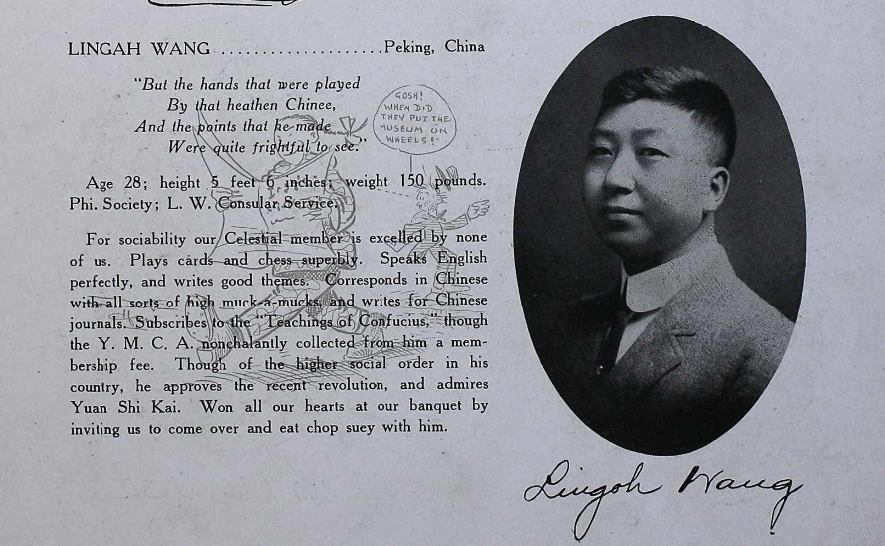

Ok, there’s definitely a lot here. This is L. K. Wang’s senior photo in the University of North Carolina yearbook, along with a tongue-in-cheek description of him and a cartoon illustrating his character drawn in the background. The cartoon makes it hard to read the text, and the text makes it hard to see the cartoon, which is annoying. The cartoon is of a stereotypical Chinese man, with Manchu queue – a hairstyle L. K. Wang did not have – strolling along reading the newspaper. A man in Western dress sees him and exclaims, “Gosh! When did they put the museum on wheels!” The text reads: “Age 28; height 5 feet 6 inches; weight 150 pounds. Phi. Society; L. W. Consular Service. For sociability our Celestial member is excelled by none of us. Plays cards and chess superbly. Speaks English perfectly, and writes good themes. Corresponds in Chinese with all sorts of high muck-a-mucks and writes for Chinese journals. Subscribes to the “Teachings of Confucius,” though the Y. M. C. A. nonchalantly collected from him a membership fee. Though of the higher social order in his country, he approves the recent revolution, and admires Yuan Shi Kai. Won all our hearts at our banquet by inviting us to come over and eat chop suey with him.”

A few notes: everyone’s height and weight was listed, so this is not a slam on L. K. Wang’s weight specifically, “Celestial” refers to the Celestial Empire, the comment about Confucius vs. the YMCA highlights the fact that many Boxer Indemnity Scholars were Christian, Yuan Shikai was admired by most Boxer Indemnity Scholars and they were all most distressed when he tried to restore a monarchical system in China, and the comment about writing for Chinese journals is most likely a reference to his article “The Problem of Raising Capital for China’s Economic Development”, published in the Chinese Students’ Monthly in the spring of 1912.

So, L. K. Wang enrolled as a senior in the College of Arts of the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill (University of North Carolina Catalogue 1911-1912, pg. 216). He graduated that spring with a BA (Battle, K. P. (1912). History of the University of North Carolina Vol. 2, pg. 818). Then he returned to China that July. There are a few alumni records of him: the MIT Alumni Record of 1912 lists him as having returned to Peking (pg. 513), while the 1918 Tsinghua Returned Chinese Students Directory notes that he got married in 1914 and had one son. Our Chinese source mentions that he became the Hubei Foreign Affairs Bureau Chief, information that is echoed by the 1918 Directory. He served on several committees in and around Beijing, and then began working for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in 1917.

His first posting abroad was as the Chinese consul at Vancouver. Thanks to the unstable political situation in China at the time, his tenure was a bit more exciting than he probably expected. In September of 1918, L. K. Wang witnessed a political assassination on the streets of Victoria. Tang Hualong, a founding member of the Republic of China, was on a North American tour and ended his trip in Victoria, where L. K. Wang hosted him. On the night of 1 September 1918, Tang, his secretary Ho Te Hui, a student from the University of Washington named Fei Lin, and L. K. Wang, were leaving a banquet in Victoria’s Chinatown, when Wong Chong, a local barber, jumped out in front of the party holding two revolvers and shot Tang dead. The rest of the party scattered, pursued by the barber: “[L. K.] Wang, an old and heavy man with a bald head, ran at remarkable speed as Wong was chasing and shooting at him from behind” (“An Assassination in Victoria”, 31 Aug 2008). Sidenote: He was 40 and not even that fat!!! Anyway, L. K. Wang escaped, as did the rest of the party save Tang, and it was later discovered that the gunman was a member of the Chinese Nationalist League and an enemy of the Beijing government. L. K. Wang then promptly took a vacation to Ithaca, New York (link to entry paperwork).

In 1919, L. K. Wang was moved to the United States, serving as the second secretary of the Chinese Legation there. Then, thanks to another murder (more info here if you are interested), he was made head of the Chinese Educational Mission, the organization that kept track of Chinese students in the United States (The Washington Post, 16 Feb 1919, pg. 19). He served there until 1921, then returned home to China.

He continued working for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs from 1921-1924, living on Lin Li Chang Street in Beijing (Cornell Alumni Directory 1922, pg. 341). Then he was posted to the Philippines in 1926, serving as the consul general. There were no murders this time, but his tenure there was also rocky. He became very concerned with the issue of illegal Chinese immigrants in the Philippines, arguing that many people of Chinese heritage in the Philippines at that time had been smuggled in by large human trafficking companies, that the smuggling itself was in reaction to the US Chinese Exclusion Act, and that the Chinese populace was a benefit to the Philippines economically. He also noted that the way to stop Chinese emigration was to improve the situation in China itself (The China Weekly Review, 3 Dec 1927, pg. 2). He became so concerned with the issue that he began to meet with legislators in an attempt to block a bill that would require the registration of all Chinese persons in the Philippines. The bill was in fact rejected in late 1927 (Chicago Daily Tribune, 14 Nov 1927, pg. 16). L. K. Wang was then transferred to Batavia, in Java (The China Weekly Review, 07 Jan 1928, pg. 145).

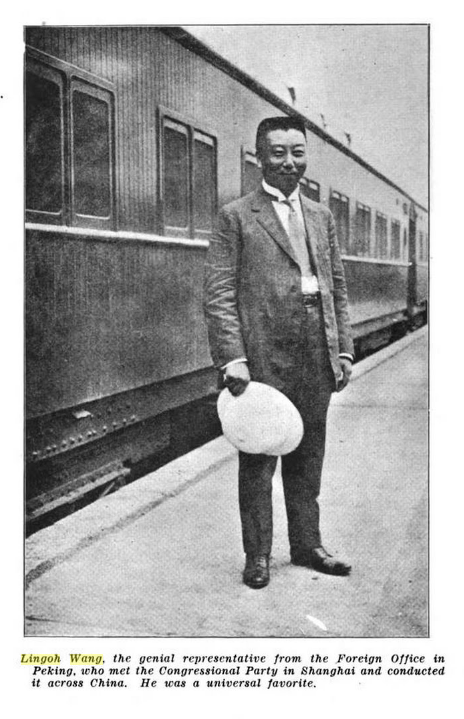

In 1928, he was moved again, this time to Europe. He entered the UK at Plymouth on 23 December 1928 (link to entry paperwork), and then went on to Spain. He began his posting on 30 December 1928 and served through 1931 (國民政府職官年表(一), pg. 557). Both MIT and Cornell catch up with him here (MIT Chinese Alum. 1930; Cornell Alum. 1931, pg. 927). In 1932 he participated in a special session of the League of Nations (League of Nations Photo Archive), and then was posted to Guatemala in 1933. Finally, in 1936, he retired from diplomatic service and returned to China via Southampton (link to exit paperwork).

By this point, he had been out of the country for close to 12 years. Shen Bao reported on his return:

神州社云、我國駐美中部領事王麟閣、服務外交界二十餘年、曾任天津交涉員、及駐歐亞美各地領事、現任美洲中部總領、於日前返國省親、現庽四川路新亞酒店、神州社記者特林訪晤、據王氏稱渠離國已十二載、此次歸來、感覺國內非特物質方面大有進境、即人民精神亦與昔逈異、深為欣慰、渠在外交界服務已二十餘載、曾作兩次全世界旅行、各地僑胞對祖國極為關心、舉凡國內天災人禍、僑胞均能慷慨解囊、樂於捐輸、加脫馬來及美洲中部華僑、數逾千人、大部均係經商、而以茶絲案佔多數、美洲中部當局待遇華僑極好、僑胞與當地人民國情、亦極融洽、僑胞因經營獲利、生活頗優裕、對祖國益為關心、

Translation: Shenzhou, Sheyun: China’s consul in the United States, Wang LinGe, has served the diplomatic community for more than 20 years, once serving as a Tianjin correspondent, as well as serving as Chinese consul in Europe, Asia and the United States. He is the current general manager for Chinese interests in Central America. He returned to the provincial capital a few days ago, and now lives at Sichuan Road, Xinya Hotel, Shenzhou. This reporter’s interview: according to Mr. Wang, he has been away from the country for 12 years. This time, he feels that not only is there a great advance in domestic resources in China, but the people’s spirit is also different from the past, and he is deeply gratified by this. He has served in the diplomatic service for more than 20 years, has made two world trips, and has seen the concern the overseas Chinese have for the motherland. In times of natural disasters and man-made disasters in the country, the overseas Chinese are generous and willing to donate. There are more than 1000 overseas Chinese in Malaysia and Central America, and most of them are doing business, mostly in the tea and silk trade. The Central American authorities treat the overseas Chinese very well, the overseas Chinese and the local people are in a good state of affairs, and they are very harmonious. The overseas Chinese are profitable from their operations, their lives are quite good, and they care about the motherland.

– Shen Bao, 8 March 1937, pg. 10

A similar article ran in the English-language press (The China Press, 07 Mar 1937, pg. 9)

So, L. K. Wang was retired from government service, and he entered the private sector, working in the banking field. He moved to Hong Kong and it wasn’t long before he began his international travels again. But then, in 1940, disaster struck, ending L. K. Wang’s life.

LINGOH WANG LOST AT SEA: Chinese Banker Disappears Off Ship From Hong Kong to Manila

Wang, 56 years old, Chinese banker of Hong Kong and former official of the Chinese National Government, disappeared last night from the liner President Pierce, ship’s officers announced today. They expressed the opinion he was lost at sea.

Mr. Wang formerly was consul general to the Philippines and once served as Minister to Spain. He was en route to Manila from Hong Kong on a business trip.